Tyler Graphics: The Baroque Phase

///national-gallery-of-australia/media/dd/images/161372_pm_-_Large_Viewing_JPEG_4200px.jpg)

David Hockney, Kenneth Tyler, Tyler Graphics, Ken Tyler 1978, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Orde Poynton Fund 2002, © David Hockney

In the newly published Tyler Graphics Catalogue Raisonné 1986–2001 DR JANE KINSMAN discusses the building of a collection that represents one of the most comprehensive records of a pivotal moment in printmaking history.

In 1973, the art critic Robert Hughes alerted the inaugural National Gallery Director James Mollison to a collection of proofs the legendary printer and publisher, Kenneth Tyler was looking to sell. Mollison, recognising the collection’s value, negotiated directly with Tyler, ultimately acquiring over 7400 works and extensive archives spanning four decades of Gemini G.E.L. and Tyler Graphics.

The workshop is magical…it’s inventive, surreal. It’s ever changing.1

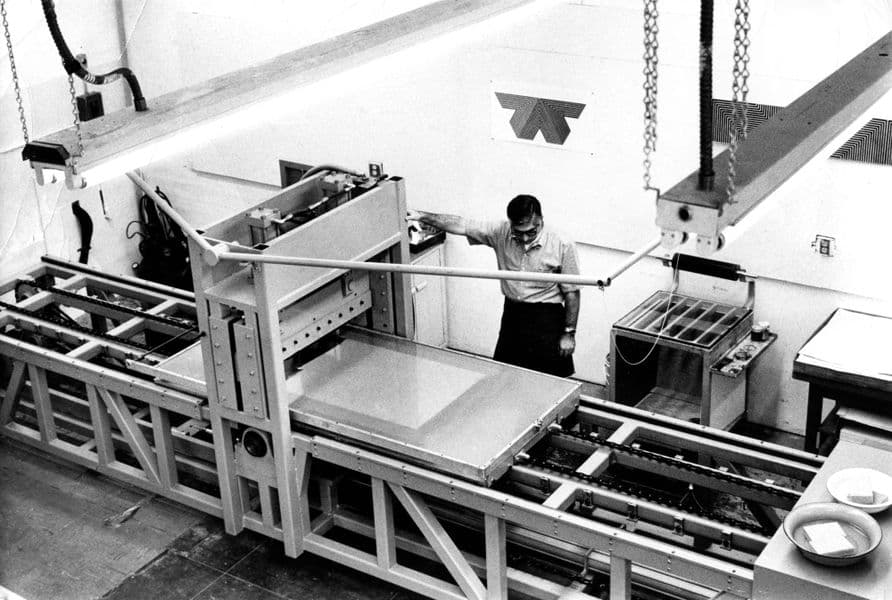

From the 1960s until the turn of the century, printer and publisher Kenneth E Tyler AO collaborated with some of the most talented artists in the United States, as well as mentoring others in the American art scene. By invitation, enticement or persistent cajoling Tyler created a stable of practitioners he chose for their skills as artists rather than as printmakers — inspired by William Lieberman’s mantra that great prints are made by great artists.2 This was a time of innovative and revitalised printmaking, in which processes had become technically complex and new materials adopted, and artists came to rely on the technical support of a master printer. Partnerships between artists and printers flourished, and Tyler was to play a significant role in this American ‘print renaissance’.3

The term ‘renaissance’ is used to convey the importance of the era—the emphasis placed on lost skills and knowledge, as well as innovative ideas, drawing on the past and building on the new. A revitalised sense of imagination and creativity were embraced by artists in collaboration with printers and led to a revolutionary phase of modern printmaking at locations such as Tyler’s workshop. In a series of Harvard lectures published in 1986 Frank Stella told of the demise of contemporary abstraction.4

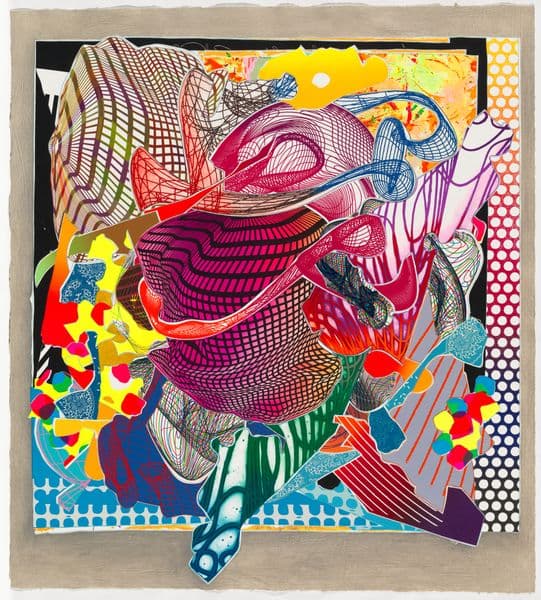

Frank Stella, Tyler Graphics (printer and publisher), Feneralia, 1995, from the Imaginary places series, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund 2002, © Frank Stella. ARS/Copyright Agency

///national-gallery-of-australia/media/dd/images/120728_apm_-_Large_Viewing_JPEG_4200px.jpg)

David Hockney, An image of Celia 1984-86, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund 2002, © David Hockney.

This analysis — coming from the leading American abstractionist — appeared almost a volte face and was considered ‘a bombshell’ by American critic Hilton Kramer in the Atlantic Monthly.5 It was Stella’s assessment that abstract art was moribund and could be compared to the dull vestiges of the late Renaissance. For the artist, the next phase was required to reinvigorate the art of modern times, one comparable to the Baroque period. Scholar Richard Axsom has aptly described Stella’s own change of style as ‘Baroque exuberance’.6

At this stage, not all artists dramatically transformed their art to the degree Stella had done, when he created a radical style in reaction to what he considered to be the limitations of modern abstraction. However, from the mid-1980s, a new phase in modern printmaking evolved for the many artists working with Tyler.

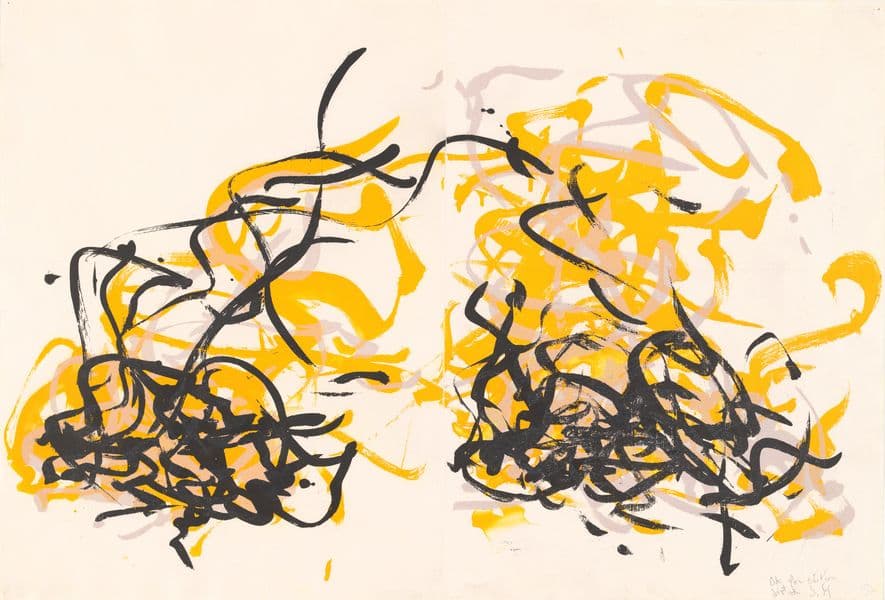

Joan Mitchell, Tyler Graphics (printer and publisher), Weeds I, 1992, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund 2002, © Estate of Joan Mitchell.

Robert Motherwell, Tyler Graphics (printer and publisher), Elegy sketch proof variation XII, 1987-90, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of Kenneth Tyler 2002, © Dedalus Foundation, Inc. VAGA/Copyright Agency

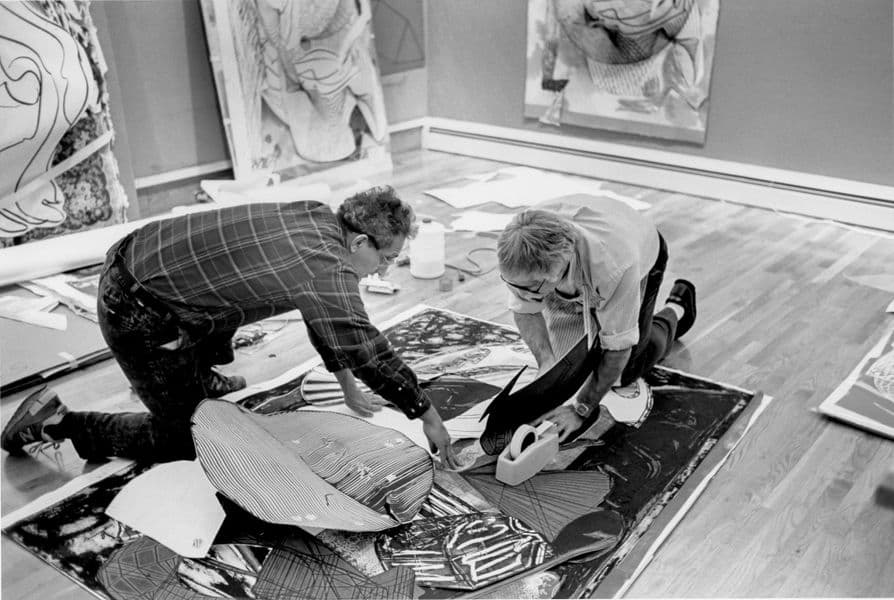

This evolution was facilitated by the experimentation, the growing expertise of his workshop and the maturity of artists who were part of the Tyler stable. This phase was characterised by a focus on the depiction of space and movement and the adoption of new colour palettes. This was combined with radical change in the construction of matrices and new methods of papermaking. These artistic and technical changes heralded the next chapter in the development of the modern print renaissance. Gone were the days where Tyler’s role was to be Josef Albers’s ‘hands’. His workshop had become something ‘magical’. As Tyler recalled of his years developing a successful workshop:

Remember that the workshop is magical. It’s a magical place. It’s inventive, surreal. Is ever changing, and the environment is always different, depending on who’s been there, and who has left. Sometimes, I would change the stage set and make it look like it’s brand new, and other times I wouldn’t bother. I gave up a long time ago trying to make it a nice clean environment for the artist to come in and work and to not have the influence of the previous person being there.7

Tyler abandoned the ‘clean sheet’ approach and showed his visiting artists what had been made at the studio previously. They seemed keen to learn of recent projects and technical breakthroughs, and the vestiges of work by a recently departed artist could become ‘building blocks’ for a newly arriving artist, providing clues, cues and fresh directions.

Many of the artists who attended the Tyler workshop came to view the experience as a means of developing new ideas and printing methods. In these adventurous times, and to provide a wider range of materials and techniques, Tyler sought out external collaborators in various companies to help develop ideas for these artists and guide the workshop’s own development. Other artists were less engaged with this approach. Tyler spoke of the range of responses:

It was always interesting to me how some artists I collaborated with, and that relationship just stayed and sometimes grew, but sometimes they didn’t at all. With Richard [Serra] I didn’t seem to hit it off that well…his agenda was different from mine in many ways. I just wanted to collaborate, and he just wanted to make things that were bigger than usual.8

David Hockney, by contrast, relished the workshop space and its potential and was the only artist to work in all four of Tyler’s workshops in the United States. As respite, Hockney chose more intimate, handmade methods of printing on occasions, creating prints at home from faxes and home printers, adopting hand tools for crude intaglio prints, and ultimately turning to digital processes including those of a smartphone. Hockney was significant in the history of Tyler publishing as he was both an accomplished artist and technically adept. Tyler considered him ‘one of the most process-minded artists to collaborate in a workshop’.9

Frank Stella and Kenneth Tyler working on a collage, Tyler Graphics Ltd., Mount Kisco, New York, 1988. Photo by Marabeth Cohen-Tyler.

Ken Tyler operating his newly designed hydraulic lithography press at Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles, California 1968. The flat and consistent areas of colour that this press created became a signature for the workshop at the time. Unknown photographer

Over the years Hockney developed new methods of depiction and experimentation producing a stylistic change, which embraced new concepts of space, and adopting a brilliant palette worthy of Matisse. When Hockney became focused on landscape compositions and working en plein air, Tyler created a new matrix, a kind of sketchbook made up of bound mylar sheets on which the artist could sketch directly. Aided by Hockney’s ability to visualise a composition in layers of separate colours, these could then be transferred to metal plates for printing. These sketchbooks played an important role in Hockney’s Moving Focus series. From 1984 to 1987 the artist made 29 prints with Tyler for this series, in bolder, more mature compositions, adopting multiple viewpoints, rather than the traditional Renaissance one-point perspective, drawing on Hockney’s own studies of Picasso, Cubism, and Chinese scroll painting, while also taking an interest in photo collage and theatre design.

This is an edited excerpt from essay ‘The Baroque phase of the Tyler workshop’ by Dr Jane Kinsman, from the publication Tyler Graphics Catalogue Raisonné 1986–2001, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025, available at the National Gallery Art Store and all good book stores.

Works of art from the Kenneth Tyler Collection are on view in Proofs and Processes: The Kenneth Tyler Collection until 28 June 2026.

References

- Kenneth Tyler, in conversation with David Greenhalgh, Lakeville, Connecticut, 9 September 2022. An abridged and edited version of this interview can be found at nga.gov.au/storiesideas/reflections-on-a-life-in-print-kennethtylerin-conversation, information management file 22/0013 National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/ Canberra, p 2.

- Kenneth Tyler, recalling a 1965 lecture by curator William Lieberman in Reaching out: Ken Tyler, master printer, 1976, film, Avery Tirce Productions.

- Riva Castleman adopted this term to describe late‑modern printmaking in Printed art: a view of two decades, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1980, p 6, as did Pat Gilmour in Ken Tyler, master printer, and the American print renaissance, Hudson Hills Press, New York, in association with the Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1986

- Frank Stella, Charles Eliot Norton Lecture Series, Harvard University, published in Frank Stella, Working space, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1986.

- Hilton Kramer, ‘The crisis in American art’, The Atlantic, October 1986, p 94, https://cdn.theatlantic.com/media/ archives/1986/10/258-4/132588289.pdf.

- Richard H Axsom, in Richard H Axsom and Leah Kolb, Frank Stella prints: a catalogue raisonné, Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, in association with the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, 2016, p 19.

- Tyler, in conversation with Greenhalgh, p 2.

- Tyler, in conversation with Greenhalgh, p 17.